Held Information

Dates: October 27 – December 10, 202

Location: Joseloff Gallery at the University of Hartford (Connecticut, USA)

Komatsu Hiroko: Second Decade

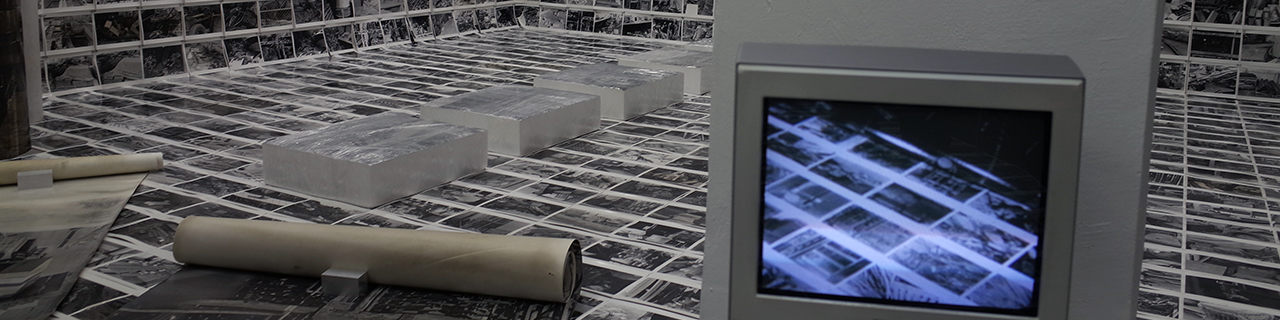

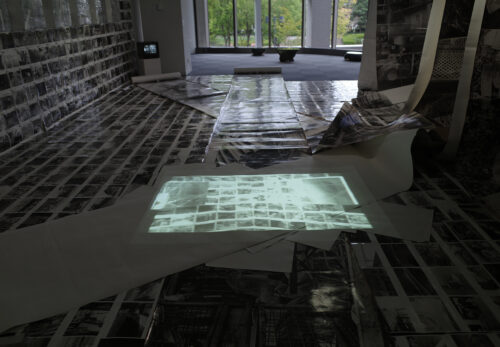

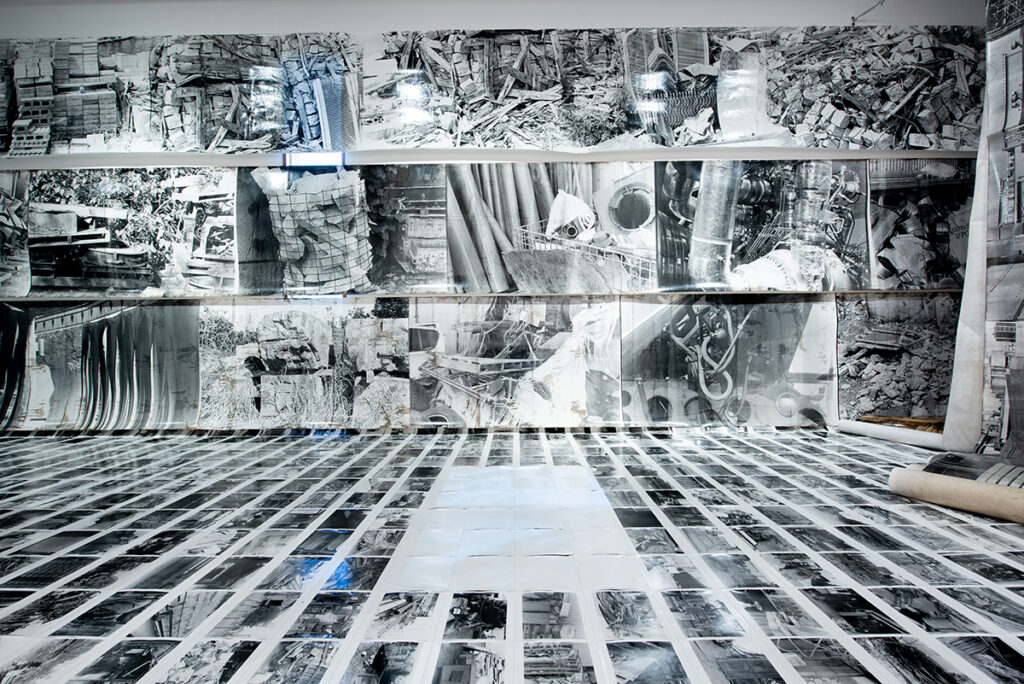

Around the globe in recent years, the Japanese photographer Komatsu Hiroko has become known for her experimental installations that transform traditional gallery spaces into worlds of monochrome. Grids of 8 x 10 photographs line walls and floors. Larger prints, obscured by plastic wrap, stretch over boxes to create sculptural protrusions. Larger still are the large uncut rolls of photographs that hang across wires and unfurl underfoot, while scenes from past installations appear via projection and loop on a CRT monitor. This material overload acts as a proxy for the photographic subject matter itself—new construction and scrap materials that flow through sites of industry. Unveiling the environmental chaos and excessive waste that undergirds processes of urban renewal in her home city of Tokyo, Komatsu creates a space to consider the cycles of creation and destruction that define the twenty-first century city.

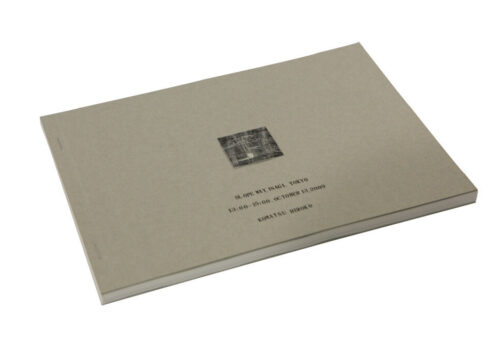

Building on recent iterations of this work at dieFirma in New York City and the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, this exhibition combines Komatsu Hiroko’s immersive photographic installation with work in a variety of other media, including handmade artist books, drawings and photograms, and 8-mm film. All were made since the year 2020—the start of Komatsu’s second decade as a committed photographer.

It is often said that Komatsu Hiroko confronts us with “things that cannot be seen,” and, indeed, we are forced to rely on senses other than vision to make sense of her work. Nothing communicates as we expect it should. Lines of text are meticulously cut out of books and contained in glass bottles; frottage rubbings and their photogram counterparts distort notions of photographic evidence; and documentary videos of musical concerts are soundless. In all cases, Komatsu pushes the materials that she is working with to their limits, asking important questions about how we produce, consume, and share knowledge; what is taken for granted in those processes; and how we might do so differently going forward.

Komatsu Hiroko (b. 1969 Kanagawa, Japan) is an award-winning artist who has held exhibitions in Japan, Germany, Italy, and the U.S. Her work has been published in Aperture, Asahi Camera, and Artforum, among other journals, monographs, and exhibition catalogues. In 2018, she was the recipient of the 43rd Kimura Ihei Award for new photographers in Japan. Her work is held in the collections of The MAST Foundation in Bologna, Tate Modern in London, the Kawasaki City Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the New York Public Library.

Curated by the Edith Dale Monson Gallery Director and Curator, Dr. Carrie Cushman, this exhibition is supported by the Joseloff Gallery Programs Fund and the Edith Dale Monson Gallery Director Curator Fund held by HAS Endowment, Inc.

Throughout the exhibition, names have been written according to Japanese convention with the individual’s surname followed by their given name.

The First Decade

By her own admission, Komatsu Hiroko came late to photography. She began her career as an experimental musician and only started working with photography in the mid-2000s after participating in a photography workshop led by Kanemura Osamu. Feeling that she needed to “catch up,” from 2010 to 2011, Komatsu rented an abandoned retail space in Tokyo to stage a series of exhibitions under the collective title “Broiler Space.” Forcing herself to execute one new exhibition per month for the entire year, Komatsu quickly ran out of usable space and had to reconsider the parameters of traditional exhibition design. And so was born Komatsu Hiroko’s singular installation method.

In “Broiler Space,” Komatsu expanded out from the walls to drape photographs across the floor, hang them from the ceiling, and, on one occasion, even roll them outside. Since then, her massive grids of 8 x 10 prints have continued to grow, adapting to the particulars of the gallery and museum spaces around the world in which they are shown. Within a single installation, no image ever repeats. Her more recent addition of videos that screen footage from previous shows enhances an atmosphere of information overload. Komatsu’s ability to maintain this tremendous output demands a rigorous regimen. She regularly visits industrial sites with her Leica camera, snapping thousands upon thousands of photographs to then develop and print in the bathroom of her apartment.

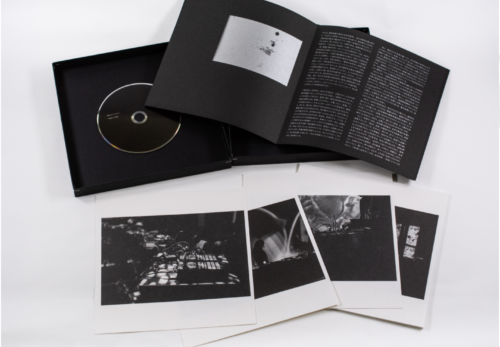

While her acclaim in the world of photography has grown, Komatsu is far from complacent, always pushing herself to experiment with new media. Her first handmade artist book, Book #1, was published in 2016. Like the walls of the gallery, here, too, she began to test boundaries, incorporating unlikely materials such as plastic wrap, tracing paper, and glass bottles into her books. Her new work with photograms and 8-mm film—on view here for the first time in the U.S.—is equally surprising and enlightening. One cannot help but wonder what she has in store for the decades to come.

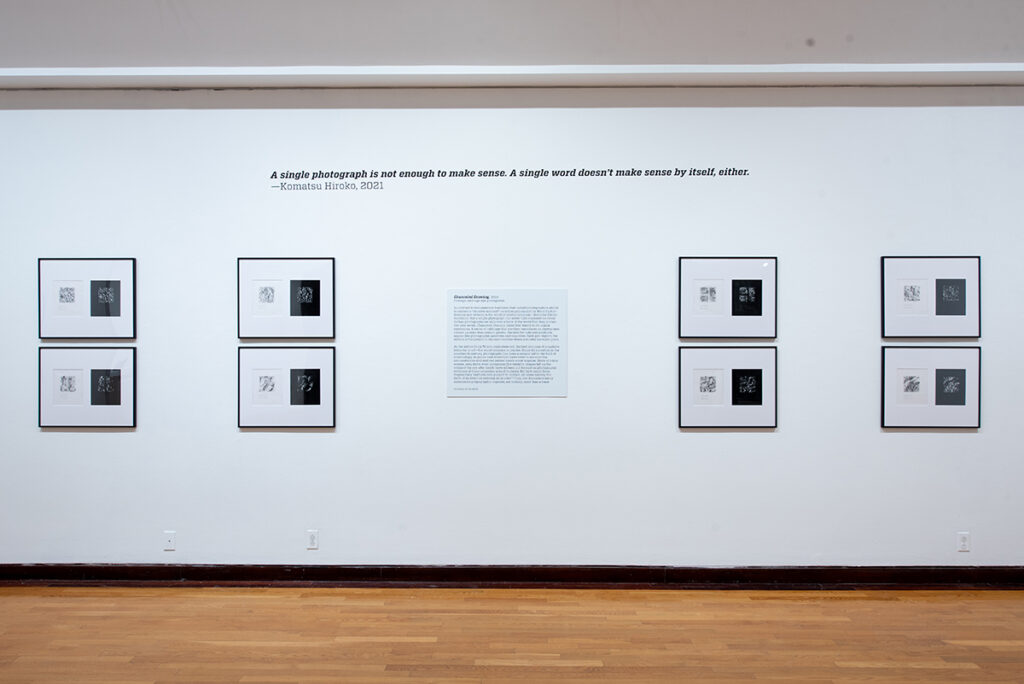

A single photograph is not enough to make sense. A single word doesn’t make sense by itself, either. – Komatsu Hiroko, 2021

自律速度錯誤 / Self-Slowing Error, 2021

Multi-media installation

While traditional exhibition displays encourage visitors to “read” individually framed photographs in succession, Komatsu Hiroko’s installations continually pull us back to the totality of the environment, where the materials of photography become just as important for communication as the images. Komatsu compares the way that photographs convey meaning to the way that language functions, specifically the Japanese written language. The title for this installation, Self-Slowing Error, includes six characters, or kanji: 自 (oneself), 律 (rhythm), 速 (speed or velocity), 度 (an indicator of degree, or number of occurrences), 錯 (disordered), and 誤 (mistake).

Individually, each character has meaning independent of the others, but as a group they do not add up to anything familiar in the Japanese language. This is intended to generate an unstable, troubled feeling in the reader, as one is forced to pull apart the characters (and, likewise, the photographs) to consider their existence as fragments of meaning. In overriding our understanding of how photographs typically convey information, Komatsu asks us to consider the potential for multiple perspectives and indeterminate meanings for crafting a different encounter with the world.

This installation comes to the University of Hartford from the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Wellesley, Mass., where the exhibition Komatsu Hiroko: Creative Destruction (February 1 – June 5, 2022) was supported by a grant from the Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission.

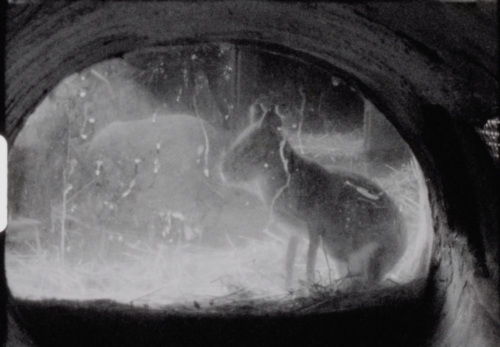

Channeled Drawing, 2022

Frottage rubbings and photograms

In contrast to documentary traditions that uphold photography’s ability to capture a “decisive moment”—a notion popularized by Henri Cartier-Bresson and revered in the world of photojournalism—Komatsu Hiroko maintains that a single photograph can never fully represent an event. Rather, photographs are only ever a trace of the world that they picture. Her new series, Channeled Drawing, takes that theory to its logical conclusion. A series of rubbings that she then reproduces as photograms (direct, camera-less contact prints), the side-by-side compositions appear like photographic positives and negatives. Each pair depicts the surface of the ground in the exact location where a murder has taken place.

As the author Colin Wilson once observed, the best outcome of impulsive behavior is art—the worst outcome is murder. Since its invention in the nineteenth century, photography has been a natural aid to the field of criminology, as police and detectives have tried to uncover the circumstances and motives behind man’s worst impulse. Shots of crime scenes, mug shots, even optograms (the belief in images left on the retina of the eye after death) have all been put forward as photographic evidence of these senseless acts of violence. But how could these fragmentary methods ever purport to contain, let alone convey, the facts of an event so extreme as murder? They, like Komatsu’s eerily mesmerizing topographic imprints, are nothing more than a trace.

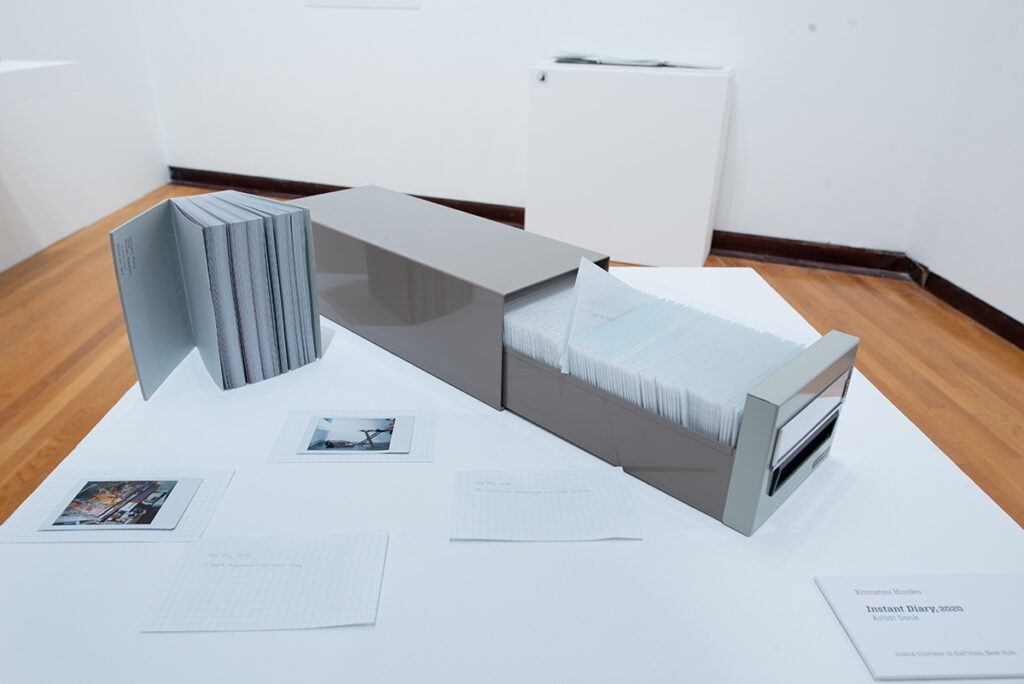

Artist Books, 2020-2021

Handmade, multi-media artist books

Books have become a fruitful medium for Komatsu Hiroko to explore the similarities between language and photography. Of her recent work, Black Book #1, she has said, “When you take a picture, you frame a part of reality, and then you move the image to another place, such as an exhibition venue or bookstore. I thought the process was very similar to cutting out texts from a book and putting them in an object—in this installation, a bottle.” Notably, the texts that she cuts and relocates come from manifestos related to ecological crisis and environmental degradation—Theodore Kaczynski’s Industrial Society and Its Future: The Unabomer Manifesto (1995), as well as the more optimistic No One is Too Small to Make a Difference (2019) by Greta Thunberg.

For Komatsu, meaning is generated from the totality of the book—and the book viewing experience—rather than through a succession of individual images or snippets of text. Her artist books are entirely handmade from unexpected materials that encourage exploration. While Instant Diary is organized according to the calendar year, viewers can enter at any point to uncover traces of the artist’s daily life, just as one would pick through the contents of a card catalog. Meanwhile, by printing on tracing paper in corrosion, images from distinct pages merge and transform into new compositions depending on the direction in which they are viewed. Here, the opportunity for multiple (even competing) perspectives takes priority over any linear narrative that we might attempt to glean from the book.

I can hear the sound of my body when I place myself in a very quiet environment. As I focus my attention to the sound, I start to lose the sense of whether the sound is coming from outside or inside my body. I feel a sensation as if my body melts into air. – Komatsu Hiroko, 2021

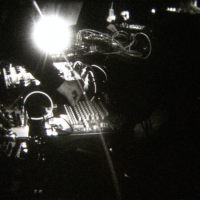

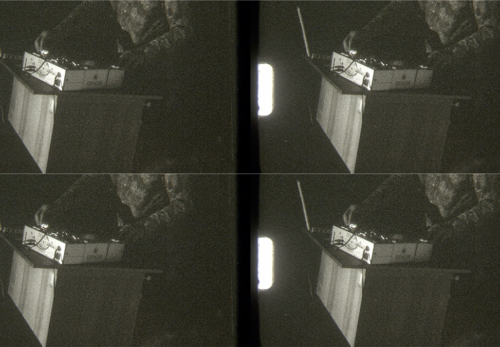

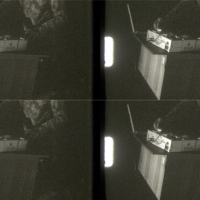

Silent Sound, 2021

8-mm film installation and gelatin silver prints

In 1951, the composer John Cage entered an anechoic chamber at Harvard University to experience silence. Instead, he heard the high-pitched sound of his nervous system and the low thrumming of his blood flow. These unintentional and uncontrollable noises became the basis for his theory of silence, exemplified by the composition 4’33”, in which Cage had a musician sit at a piano without playing it for 4 minutes and 33 seconds.

Here, Komatsu performs a similar move by presenting three 8-mm films that she recorded of experimental noise concerts by 3RENSA (the combined forces of Merzbow, duenn, and Nyantora)—all without sound. Focusing on silence turns the locus of the aesthetic experience from the creator to the audience. It also nudges the audience to attend to their full capacity as perceiving beings—to the sights, smells, and, yes, the sounds of their bodies that hum along with that of the projectors. Space and time are marked by the film as it moves out from the projector and loops through a series of pulleys affixed to the wall and ceiling. Running continuously over the course of the exhibition, the film will necessarily deteriorate, transforming into a mere trace, a fragment of the original.

Curation and Texts by Carrie Cushman